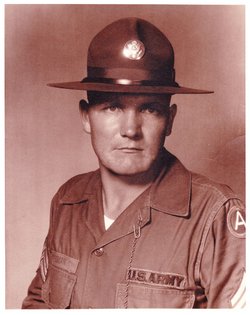

Fifty years ago this month, 28 year old, Sergeant First Class (SFC) Jimmy Grant Freeman, a native of Talladega, Alabama, and his comrade-in-arms, 33 year old, Staff Sergeant (S/Sgt) Darrell E. Anderson of Minneapolis, Minnesota, lost their lives in the steaming jungles of South Vietnam when the two men were attacked by a Viet Cong force numbering a thousand men. They died while standing back to back defending Tam Soc Operating Base on 24 March 1969.

Author, and Vietnam veteran, retired US Army Master Sergeant Ray Bows, has honored sergeants Freeman and Anderson in some of his past written works, and has memorialized them in one of his most recent books, his 800 page, In Honor and Memory: Installations and Facilities of the Vietnam War.

In 1987 Bows discovered the basis of the story of Freeman and Anderson when he located orders at the Department of the Army Records Section. Orders revealed that the two sergeants posthumously received Silver Stars for heroism, and the Freeman-Anderson Compound was named in their honor on 14 April 1970. Yet their families were never notified of the namings. Sergeant Freeman's wife, Dorothy, learned the camp was named for her husband only a few days before she died in 1988, and only through Sergeant Bows.

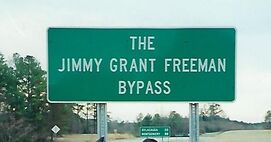

Bows, in contact with SFC Freeman's daughters, Jaime, Cindy and Dorothea, eventually had The Jimmy Grant Freeman Bypass (US Route 280 in Talladega) named in his honor, and thereafter, SFC Freeman was inducted into the Alabama Hall of Honor at Marion Military Institute, which venerates Alabama's all time greatest military heroes.

Author, and Vietnam veteran, retired US Army Master Sergeant Ray Bows, has honored sergeants Freeman and Anderson in some of his past written works, and has memorialized them in one of his most recent books, his 800 page, In Honor and Memory: Installations and Facilities of the Vietnam War.

In 1987 Bows discovered the basis of the story of Freeman and Anderson when he located orders at the Department of the Army Records Section. Orders revealed that the two sergeants posthumously received Silver Stars for heroism, and the Freeman-Anderson Compound was named in their honor on 14 April 1970. Yet their families were never notified of the namings. Sergeant Freeman's wife, Dorothy, learned the camp was named for her husband only a few days before she died in 1988, and only through Sergeant Bows.

Bows, in contact with SFC Freeman's daughters, Jaime, Cindy and Dorothea, eventually had The Jimmy Grant Freeman Bypass (US Route 280 in Talladega) named in his honor, and thereafter, SFC Freeman was inducted into the Alabama Hall of Honor at Marion Military Institute, which venerates Alabama's all time greatest military heroes.

Then, Bows was finally able to contact the Anderson family in Minnesota, and through the good graces of local veteran's organizations in the Minneapolis area, the Andersons were flown to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, in Washington, D.C., where a plaque, designed and engraved by Bows' son, Jeff, was placed at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial where it remained for one week before becoming a permanent part of the "Wall's" collection.

Bows explained, "Sergeant Freeman was home on emergency leave, because of the death of his youngest daughter, but chose to return to Vietnam, knowing that his surrounded location would be overrun at the next new moon when jungle nights were the darkest. Sergeant Anderson was back there on his own and their team did not have the support they required. Sergeant Freeman packed canned meat and other supplies into two suit cases, and left Talladega, already certain of his ultimate fate when he returned. His actions were heroism beyond the call. He had complete justification for a compassionate reassignment, but wouldn't leave Anderson on his own." Yet after all these years the Freeman story still has many gaps in it. His commander is not willing to talk about the night of 24 March 1969, when the two sergeants were killed, and Bows has learned that there were two other team members who were supposed to be at Tam Soc on the night of the attack. "I have yet been able to locate them for interviews, so that I might get the full story."

As if the powerful tale of Freeman and Anderson is not enough, Bows learned (in 1992) that four days later, on 28 March 1969, another attack occurred on another mobile advisory team, 215 miles to the north of Tam Soc.

Bows explained, "Sergeant Freeman was home on emergency leave, because of the death of his youngest daughter, but chose to return to Vietnam, knowing that his surrounded location would be overrun at the next new moon when jungle nights were the darkest. Sergeant Anderson was back there on his own and their team did not have the support they required. Sergeant Freeman packed canned meat and other supplies into two suit cases, and left Talladega, already certain of his ultimate fate when he returned. His actions were heroism beyond the call. He had complete justification for a compassionate reassignment, but wouldn't leave Anderson on his own." Yet after all these years the Freeman story still has many gaps in it. His commander is not willing to talk about the night of 24 March 1969, when the two sergeants were killed, and Bows has learned that there were two other team members who were supposed to be at Tam Soc on the night of the attack. "I have yet been able to locate them for interviews, so that I might get the full story."

As if the powerful tale of Freeman and Anderson is not enough, Bows learned (in 1992) that four days later, on 28 March 1969, another attack occurred on another mobile advisory team, 215 miles to the north of Tam Soc.

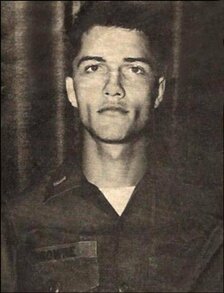

Twenty-three year old, First Lieutenant (1LT) Terry D. Graham, a native of Gainesville, Florida, along with his fellow officer, 24 year old, First Lieutenant Earl F. Browne, from New York City, lost their lives when the two men were attacked by a Viet Cong force, and their defensive bunker was overrun. They died while their position came under an intense enemy barrage as they defended Operation Base #6 at Duc Vinh in Binh Long Province.

Ray Bows, who was in Vietnam at the time of those attacks, had no idea that they had occurred. "They were never publicized," he said. None-the-less, years later, Ray discovered information about Graham and Browne after he came across a photograph of the camp at Hon Quan named in their honor. Like Freeman and Anderson both officers also posthumously received a Silver Star, and the Graham-Browne Compound in the III Corps Tactical Zone was named for them in a growing tradition.

During Ray's investigation he learned that Lieutenant Graham's family knew little about the camp named for their loved one, and it is not certain that Earl F. Browne's family was ever notified of the honor bestowed on their family member. Ray said, "New York City is a big place, and I have not been able to narrow down which borough Earl Browne grew up in, and therefore have never been in contact with his family."

Bows, however, was able to contact Graham's son, Robin Graham, long after the MACV installation had been transferred to the South Vietnamese Binh Long Province chief on 18 December 1970.

"These men were assigned to mobile advisory teams which were placed in remote villages to provide military and civic backing. To gain the confidence and support of the locals, Graham and Browne, like Freeman and Anderson were expected to live among the villagers and adopt their life style. Most such units were pitifully under-strength. These were heroes of the highest order," said Bows. "Yet after all these years the Freeman-Anderson and Graham-Browne stories have many gaps in them, and although I know much about mobile advisory teams, I am still trying to fill in the missing pieces to the puzzle. I am looking for those who served with these brave men.

"My job isn't complete in telling the mobile advisory team story," said Bows. "This is one of the most unique chapters of the Vietnam war, and men who served with MAT teams, fought and sacrificed during trying and very dangerous times as they experienced the most Spartan conditions that anyone could ever imagine. I know MAT team members were a tight knit group, who served few and far between. I probably have no better than a fifty-fifty chance of ever making the right contacts, but I won't quit. Anyone who knew any of these four men at whatever point in their lives, and in whatever capacity, is urged to contact me."

Those who have more information about Freeman, Anderson, Graham, Browne, or other mobile advisory team members, can contact Ray Bows at his website www. bowsmilitarybooks.com.

Ray Bows, who was in Vietnam at the time of those attacks, had no idea that they had occurred. "They were never publicized," he said. None-the-less, years later, Ray discovered information about Graham and Browne after he came across a photograph of the camp at Hon Quan named in their honor. Like Freeman and Anderson both officers also posthumously received a Silver Star, and the Graham-Browne Compound in the III Corps Tactical Zone was named for them in a growing tradition.

During Ray's investigation he learned that Lieutenant Graham's family knew little about the camp named for their loved one, and it is not certain that Earl F. Browne's family was ever notified of the honor bestowed on their family member. Ray said, "New York City is a big place, and I have not been able to narrow down which borough Earl Browne grew up in, and therefore have never been in contact with his family."

Bows, however, was able to contact Graham's son, Robin Graham, long after the MACV installation had been transferred to the South Vietnamese Binh Long Province chief on 18 December 1970.

"These men were assigned to mobile advisory teams which were placed in remote villages to provide military and civic backing. To gain the confidence and support of the locals, Graham and Browne, like Freeman and Anderson were expected to live among the villagers and adopt their life style. Most such units were pitifully under-strength. These were heroes of the highest order," said Bows. "Yet after all these years the Freeman-Anderson and Graham-Browne stories have many gaps in them, and although I know much about mobile advisory teams, I am still trying to fill in the missing pieces to the puzzle. I am looking for those who served with these brave men.

"My job isn't complete in telling the mobile advisory team story," said Bows. "This is one of the most unique chapters of the Vietnam war, and men who served with MAT teams, fought and sacrificed during trying and very dangerous times as they experienced the most Spartan conditions that anyone could ever imagine. I know MAT team members were a tight knit group, who served few and far between. I probably have no better than a fifty-fifty chance of ever making the right contacts, but I won't quit. Anyone who knew any of these four men at whatever point in their lives, and in whatever capacity, is urged to contact me."

Those who have more information about Freeman, Anderson, Graham, Browne, or other mobile advisory team members, can contact Ray Bows at his website www. bowsmilitarybooks.com.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed